Welcome or welcome back, dear reader.

I am in the midst of madly preparing for ten days of medieval camping shenanigans, and so have limited time to committ, but am determined to continue my regular updates nonetheless. One of the things I am most frequently approached by other people is Irish dress history, often with questions as to how to research it or what to look for. My main focus is the 16th century, but I broadly research pre-1600, and so this might not be all that helpful if you’re making a Victorian maid’s outfit or dressing as an 18th century socialite.

To those of you who are new here, g’day!

My name is Kate A J Swan and I am a higher degree by research candidate at the University of Sydney commencing a masters on 16th century Irish clothing in a few short months. I actively participate in the SCA here in Australia and use my engagement with this group as an opportunity to explore embodied practice and lived experience wearing and re-creating historical garments. I’m an experimental archaeologist with an undergraduate degree in archaeology and English, and I spent a fair bit of the English portion on Celtic studies. I research the clothing and textiles of northern Europe pre-1600, with a focus on Scotland and Ireland, and do so at the highest level I can given the resources available.

In other words, I’m pretty damn serious about this stuff.

Irish dress history is a field very much in its infancy, and as such fraught with errors, inconsistencies and debate. I’m hopeful that there is a new generation of researchers out there, seeking to fill the gap left by the great Elizabeth Wincott-Heckett, and expand upon the foundations she forged in Irish textile archaeology. But for now, it’s worth noting that there is not much material out there – at least not secondary or tertiary sources. The issue is less a lack of evidence, more lack of scholarship.

And so with that brief introduction aside, let’s get into ten top tips I have for all you passionate people with an interest in the clothing of the Emerald Isle to guide you on your research!

1. Use older texts as springboards

As per my salty literature review, I take issue with the two most frequently cited and recommended texts on this subject; McClintock and Dunlevy. There are even older texts which are often relied upon for basic information on the history of Irish clothing, such as Walker’s An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish, or Smith’s Ancient Costumes of Great Britain and Ireland – but given that these were published in 1788 and 1814 respectively, I would trust them about as far as I could throw them. Which is not far, I never was a good athlete.

If you do come across these texts, or have access to them I advise you to use them as springboards. Take note of the primary sources, whether they are visual, textual, linguistic, archaeological, that they make use of, and then look at them yourself. Draw your own conclusions.

Prior to the days of the internet, these books were often the best people outside academia could get, and were heavily relied upon as a result. But today, there are many better sources, including primary sources, which are readily accessible online and for free, and the rapid development of dress history and textile archaeology have significantly improved our understanding. You will learn far more from looking at the original sources yourself than another person’s interpretation (or misinterpretation) of them.

2. Iconography is your friend

Iconography should not be underestimated. Iconography is, essentially, a flashy word for the study of images, there is so much which can be gleaned from them. As in Scotland, there are many stone carvings in Ireland depicting human or humanoid figures in clothing, and I believe these are a largely untapped resource.

You will find examples of early medieval dress on cross slabs and stone carvings, and late medieval dress in funerary monuments. Hunt’s Irish Medieval Figure Sculpture is a fabulous book with many, many pictures, but you can also find them findagrave.com.

Don’t take someone else’s word for it when they say “this is in the Book of Kells”, especially if they don’t cite which bloody folio of the 600 pages they mean. Seriously, it’s available online and for free, check it out yourself. There are hundreds of human figures in it. Manuscripts, particularly those by foreign travellers such as Giraldus Cambrensis, often feature illustrations to accompany their descriptions of how the people clothed themselves.

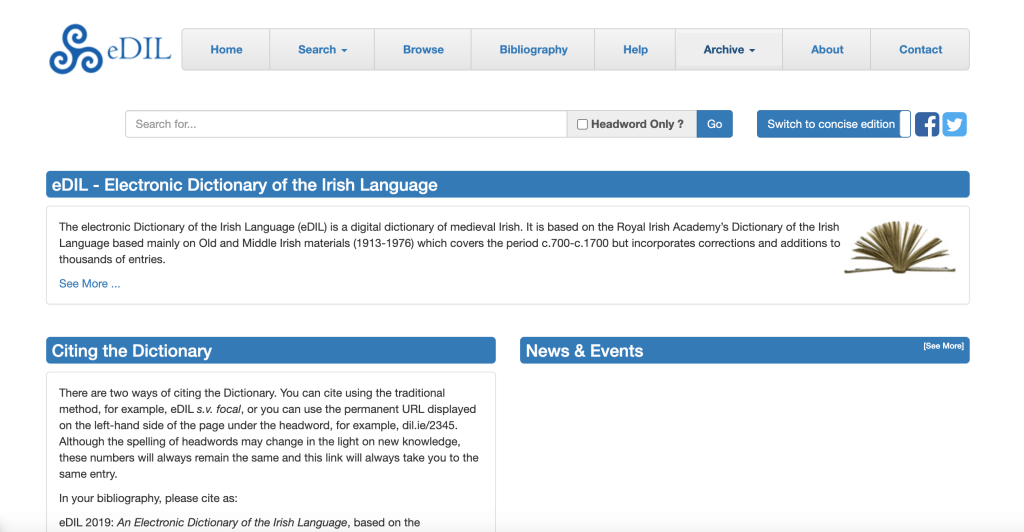

3. Use DIL, or better still, learn Irish!

DIL, or Dictionary of the Irish Language, is a must for any sort of research involving Gaelic words. Make sure when you type the word in that you tick the ‘headword only’ box or you’ll be overwhelmed. There’s even a handy guide on the website’s homepage for how to cite it. This website shows you where a word is used in historic texts and provides links to the specific sentences it’s included in – remember, context is everything.

Whilst we generally recognise that to study German historical dress, you should learn German,, Irish is often left out. Understanding the original use of local terminology will prove most useful.

4. Check out CELT

Another amazing website is CELT, or Corpus of Electronic Texts, which has been developed by University College Cork and features over a thousand texts published online, many translated, and sorted into clear categories by language, region and period in history. You don’t need to visit an archive in the British Isles to read what Gernon wrote of the Irish in 1620, or gain an indirect, chopped and changed quote taken out of context in a book.

As these texts are online, you can keyword search them, but I would highly recommend reading the whole thing as it’ll give you some vital context and a better understanding, but also safeguard against the joy that is pre-standardised spelling.

Be cautious with translations, they are inherently dodgy and were likely not done by researchers of historic dress and so the words used may be inappropriate and inaccurate!

5. Extant textiles exist – but are understudied

There are a wide array of extant textiles from Ireland, however many of these have not been studied. To this day, there is not a peer-reviewed published paper on the Shinrone gown, which is a tremendous shame. The National Museum of Ireland doesn’t have collection items viewable online like other museums in Europe, but there are images of them taken by visitors all across the internet. If you don’t have anything but an image, consider sending them an email – it worked for me in finding out about those famous platform clogs from Muckton!

Familiarise yourself with key sites and terms such as Hiberno Norse, and if you want to read thorough analysis of the textiles that have been analysed, I’d highly recommend Elizabeth Wincott-Heckett’s Textiles in Ireland.

6. Draw from adjacent cultures but don’t get carried away

People who live in adjacent areas tend to have similarities across their dress styles, but at the same time can be very different. It’s a delicate balance. Finds from England, Scotland, Wales and the continent can prove helpful in reconstructing Irish dress, particularly as Ireland was a very active player in European politics throughout the medieval period and engaged in widespread trade. Similar landscapes, agricultural products and materials can give rise to similar clothing, but also very different styles.

An example; there are descriptions of saffron-dyed léinte in Scottish contexts, but this shared style of dress does not automatically mean the Irish wore kilts. The current consensus is that they never did and this was an invented tradition from the 19th century.

7. Sumptuary indicate what people did wear, not what they didn’t

Why make it illegal if no-one is doing it? Sumptuary laws enshrine an ideal set by the ruling classes but are not by default reflected in the general populus. There are famous sumptuary laws in Brehon law which stipulate the kind and number of colours suitable for people of different rank, similarly Henry VIII limited the meterage of linen to be used in léinte across classes, but the extent to which these were followed is unclear.

In theory, a late Henrician Irish person is banned from wearing saffroned linens, but in remote areas or as a mercenary on the continent, and with the ability to prove the saffroning of the linens questionable at best – just how realistic is the application of that rule?

8. Let go of your assumptions

Watch out for romanticised and exoticised myths of “Celtic” cultures. Celtic today is of little use save as a linguistic term, but if people want to self-identify with the word then that’s up to them. Constructed and false traditions about such as county tartans and kilts (much of the clan tartan system in Scotland is also fabricated, I’m so sorry). Due to multiple waves of largescale migrations (often due to the impacts of colonialism and genocide), there is an enormous Irish disapora with particularly large populations in North America and Australia. Many, many people have Irish descent, but possessing Irish descent or a certain percentile of “Irish DNA” (the science behind a lot of these DNA testing companies is bodgy at best and they’re awful quiet about what they do with all that genetic data) does not by default make you Irish, especially if you were not raised with the culture.

In an attempt to connect to this heritage amidst the devastation of the 19th century, many Irish people and diaspora alike sought to fill in the gaps. But often times, this represents a dream and not a reality.

If your current view of Irish culture and dress is shamrocks, leprechauns, green, knotwork and Riverdance – I strongly encourage you to learn more. Ireland is a complicated island with a troubled history, and many of these scars are just below the surface. Be considerate in how you approach her.

9. Cite your damn sources

This applies to any research – cite your goddamned sources. If you want to build on knowledge and make it easier for others to follow you, cite your damn sources. Be honest if you got a quote indirectly, this helps to iron out misinterpretations and makes them easier to track. Be honest about the language you read an original quote in, translations can be dodgy. If you do not cite your sources, which in all simplicity is just stating where you got your information, you are actively preventing others from following you and making their lives harder. Surely I don’t need to emphasise how much, in this age of AI, we need to keep ourselves accountable for just where we got our information.

10. Recommended resources

- https://celt.ucc.ie/

- https://www.tara.tcd.ie/

- Book of Kells Online

- Textiles in Ireland, Elizabeth Wincott-Heckett

- Susan Flavin, Consumption and Culture in 16th-Century Ireland

- John Hunt, Medieval Figure Sculpture in Ireland

And with my heart and soul well and truly poured out into this, I shall bid you adieu.

Until next time – and enjoy your research!

Kate

Leave a comment